Breaking News

No Box for Justice: Inside Mississippi’s Broken Prison Grievance System

The Call That Said Everything

When I dialed the Mississippi Department of Corrections commissioner’s office, I expected professionalism, maybe even urgency. What I got instead was a bureaucratic echo chamber.

“This is the commissioner’s office,” the woman said.

I explained the problem — a constitutional one — about inmates at Delta Correctional Facility being denied access to grievance forms and ILAP requests. When I finished, she cut me off:

“I need to send you to the commissioner’s office.”

That’s when it hit me: in Mississippi’s corrections system, even accountability has to be forwarded.

I made it clear who I was — Don Matthews with We the People News — and that the story would run by five o’clock if Commissioner Burl Cain didn’t call me back. Only then did her tone shift. The room on the other end of the line seemed to wake up.

“I’ll have someone look into it,” she finally said.

“That’s what the people need to hear,” I told her.

And that’s where this story begins.

The Reports from Inside

Multiple sources from Delta Correctional have told me the same thing: there’s no grievance box. No ILAP box. No confidential way for an inmate to file a request or complaint.

Instead, if an inmate wants to report abuse or mistreatment, they to hand the form to a guard — possibly the very guard they are reporting. That isn’t procedure; that’s intimidation by design.

Mail? Same story. No mailbox. No locked drop point. The only “system” is giving it directly to a corrections officer on night shift.

One inmate put it simply:

“They say we can grieve, but we can’t even drop the paper.”

What the Law Says

The law isn’t vague on this. In Bounds v. Smith (1977), the U.S. Supreme Court held that prisons must provide inmates with “meaningful access to the courts.” That includes the right to file grievances and legal assistance requests.

Two decades later, in Lewis v. Casey (1996), the Court reaffirmed that right — and made clear that when prison officials obstruct it, they violate the First Amendment.

Then there’s Farmer v. Brennan (1994), which established that officials who show “deliberate indifference” to known risks or constitutional violations can be held liable under the Eighth Amendment.

So when MDOC ignores reports that inmates have no safe way to file grievances, that’s not a paperwork problem. That’s a constitutional one.

Even MDOC’s own internal policy — Administrative Remedy Program (ARP), Policy 20-08 — mandates accessible, confidential grievance procedures. “Confidential” doesn’t mean slipping a form to a guard who controls your daily life.

The Bureaucratic Deflection

When I raised these issues, the response from the commissioner’s office was not outrage, not even concern — just redirection.

“I can’t comment on that… I’ll have someone look into it.”

“He’s not in the office right now.”

The tone was polite, careful, professional — the kind of tone that gets people through their workday but never fixes anything.

If you listen closely to the call, you can hear something more subtle: a system that’s learned to protect itself. Every question gets rerouted. Every responsibility diluted. By the time it’s “looked into,” the problem has already gone quiet again.

The Cost of Silence

What’s happening at Delta Correctional isn’t unique — it’s just quieter there. At Parchman, the neglect made headlines. At Delta, it hides behind procedure.

A grievance system that doesn’t function is more than a missing box; it’s a message. It tells the men inside that their voices don’t count. It tells the guards they can act without oversight. And it tells the public that “corrections” in Mississippi still means control, not rehabilitation.

One source told me she’d never had a problem at Delta but didn’t want to be retaliated against for speaking up. That line alone says it all: when the fear of retaliation outweighs the faith in justice, the Constitution becomes a ghost in its own house.

What Comes Next

As of publication, Commissioner Burl Cain has not returned my call. His office did say they would “look into the ILA procedure” at Delta Correctional Facility.

Looking is one thing. Fixing is another.

The Constitution doesn’t take weekends off, and it doesn’t stop at the prison gate. If the State of Mississippi is serious about justice, it can start by giving its inmates something simple — a locked box, a piece of paper, and the right to be heard without fear.

Discover more from We The People News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Breaking News

Medical Dispensary Denies Disabled Marine Corps Veteran During PTSD Crisis

By Don Matthews | We The People News

On Sunday afternoon, February 8, 2026, a disturbing incident occurred at The Apothecary medical marijuana dispensary in Lafayette, LA involving a disabled United States Marine Corps veteran during an acute medical crisis. The facts are not in dispute. What happened was not loud, not chaotic, and not confrontational. It was quiet, procedural, and revealing.

Matthew Reardon, a Marine Corps veteran with service-connected PTSD, entered The Apothecary with a valid medical marijuana license that he has held since September 2025. This was his first time visiting this dispensary. He was not seeking recreational use. He was seeking prescribed medication during an active PTSD episode triggered by recent events connected to years of documented government misconduct, false charges, incarceration, and systemic retaliation.

Reardon calmly explained to the staff that he was experiencing severe PTSD symptoms and needed fast-acting relief. He asked for guidance on the most effective and cost-efficient option available because he had exactly $15 accessible on his Cash App account. He was transparent about his situation. He did not ask for free medication. He asked for help navigating a system that brands itself as medical.

The lowest-priced product available was a single pre-rolled joint priced at $12.50. At checkout, Reardon was informed that the dispensary does not accept tap-to-pay. He then attempted to pay using his Cash App card. At that point, staff advised him that their payment system only processes transactions in $5 increments, meaning the $12.50 purchase would be automatically rounded up to $15. He was then told that an additional $3.50 card-processing fee would be added on top of that amount.

Reardon explained—again—that he had access to exactly $15 and no more. He explained that this medication was necessary to manage his PTSD symptoms in that moment. He asked for a supervisor.

When the manager arrived, Reardon reiterated the situation clearly and respectfully. He requested a reasonable accommodation: any adjustment that would allow him to obtain the prescribed medication without being priced out by arbitrary rounding and discretionary fees. Options existed. The price could have been adjusted. The fee could have been offset. A managerial override could have been used.

Instead, the manager stated that nothing could be changed in the system. Staff suggested Reardon leave the dispensary, go across the street, purchase another item he did not need, and attempt to obtain cash back—an impractical and dismissive suggestion given his disclosed financial and medical condition.

At no point did Reardon raise his voice, threaten staff, or disrupt business. He did not record inside the store out of respect. He was there for medicine, not confrontation. Yet despite clear knowledge of his disability, his medical crisis, and his inability to absorb additional fees, the dispensary refused all flexibility.

This is not merely a customer service issue. PTSD is a recognized disability under federal and state law. Medical marijuana dispensaries that hold themselves out as medical providers are expected to make reasonable modifications to policies when rigid enforcement denies disabled patients equal access to prescribed treatment.

Reardon was not asking for charity. He was asking for accommodation.

What makes this incident particularly troubling is the context. Reardon has lost nearly everything due to years of government abuse, including false charges dating back to 2017, prolonged incarceration, and the seizure and sale of his personal property while he was jailed. Those same false records continue to disqualify him from employment through background checks, trapping him in financial precarity.

Against that backdrop, a medical dispensary chose strict adherence to payment mechanics over human judgment during a medical emergency.

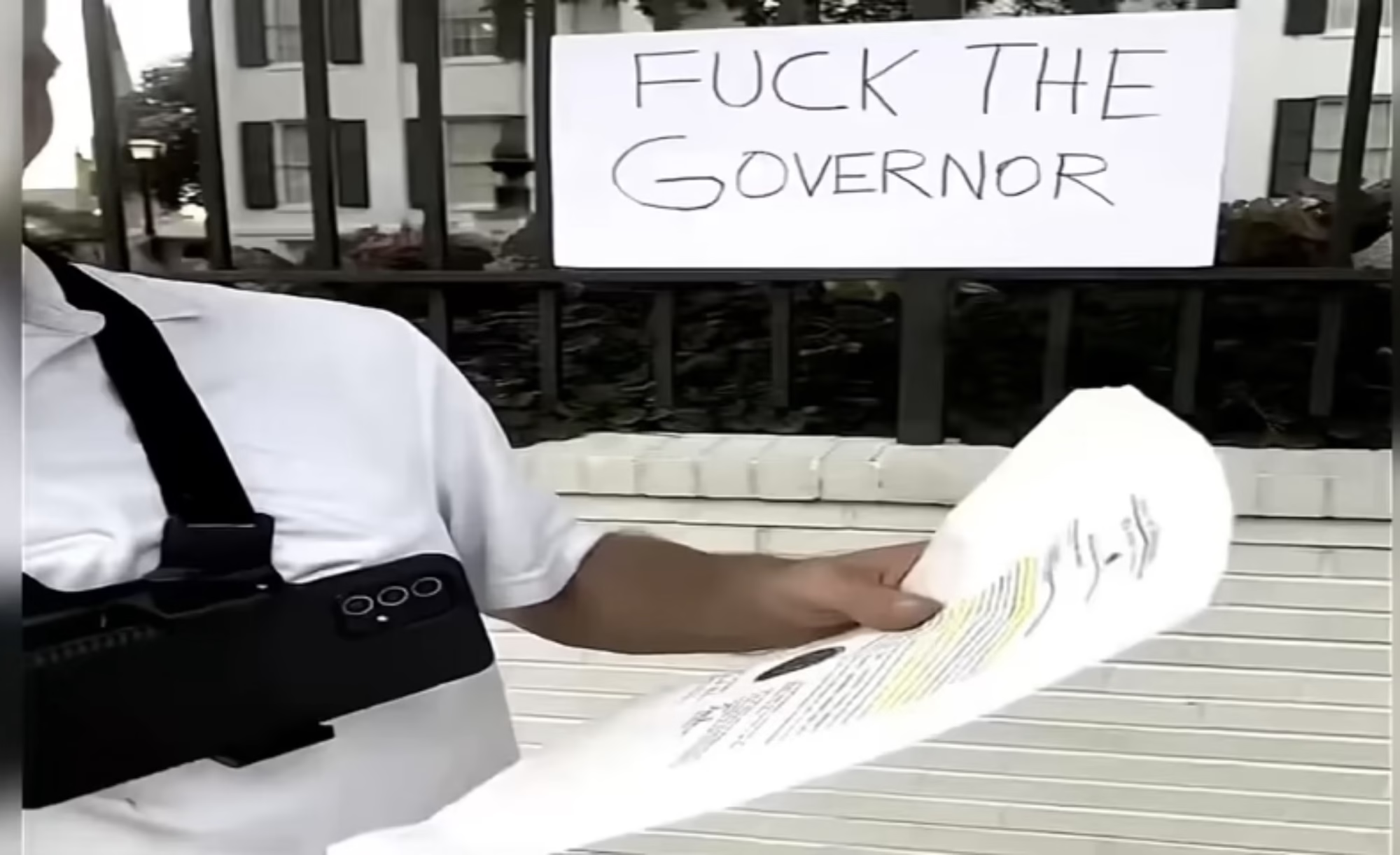

After leaving the dispensary without medication, Reardon exercised his First Amendment rights by preparing to stand on a public sidewalk outside the business.

This article exists so that members of the public who encounter that sign understand exactly what it refers to.

We The People News encourages The Apothecary to preserve all surveillance footage and transaction records from the time of this incident. Transparency serves everyone.

Medical care is not defined solely by licensure or product type. It is defined by whether institutions recognize the humanity and legal rights of the patients they serve—especially when those patients are disabled veterans seeking relief during a crisis.

This report is factual, contemporaneous, and accurate to the best of our knowledge. Any party wishing to dispute the facts is encouraged to do so with evidence.

— Don Matthews Reporting on the experience of Matthew Reardon

Discover more from We The People News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Breaking News

Exclusive: FBI database allegedly accessed by Red Cross shelter after man sought shelter during winter storm

At the center of the controversy is a question with implications far beyond one individual case: Are emergency shelters being used—intentionally or not—as gateways for law-enforcement screening, and are federal criminal databases being accessed outside lawful purposes during crises?

A winter storm emergency shelter publicly advertised as open to anyone—“no registration, no screening”—has now become the focus of a federal complaint alleging misuse of one of the United States’ most sensitive law-enforcement databases.

The incident occurred on January 24, during a period of freezing temperatures in Louisiana, when Lafayette Consolidated Government opened warming shelters for the public. Local media broadcasts emphasized that anyone needing warmth could simply show up. The shelter at issue was operated by the American Red Cross, a private humanitarian organization.

According to a formal report now submitted to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, events that followed raise serious questions about whether a federal criminal-justice database was accessed or leveraged after a private citizen sought shelter during the emergency.

From Humanitarian Aid to Law-Enforcement Action

The reporting individual states that he entered the warming shelter solely to escape freezing conditions, relying on public assurances that no identification, registration, or screening was required. He was not suspected of a crime at the time and was not informed of any law-enforcement involvement at the shelter.

Shortly thereafter, law-enforcement action was taken against him based on what was described as an “NCIC hit” connected to an unfinished or questionable warrant originating from New Orleans. The arrest was carried out publicly, and the individual was jailed.

The National Crime Information Center (NCIC) is a federal database operated by the FBI through its Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS) division. Access is strictly limited to authorized criminal-justice agencies and may only be used for legitimate criminal-justice purposes. Private entities, including nonprofit organizations, are not authorized to access NCIC or request queries.

Legal experts note that even sworn law-enforcement officers may not lawfully access NCIC for non-criminal purposes, including background screening, risk assessment, or requests initiated by private parties.

Why Consent or “Safety” Does Not Apply

Federal law and CJIS policy are explicit: NCIC access is governed by statute and regulation, not by consent. Even if a private organization claims safety concerns or cooperation with police, those rationales do not authorize criminal-history checks outside a lawful investigative context.

Improper access or dissemination of NCIC data can trigger severe consequences, including administrative sanctions, loss of database access, and potential criminal exposure.

Missing Property and Escalating Harm

The situation escalated further after the arrest. According to sworn statements, the individual’s personal property was handled in two separate ways. While his jail property was inventoried, a backpack was seized separately by Lafayette Police and booked into the department’s evidence room.

When the backpack was later returned, his car keys were missing.

The keys had not been inventoried at the jail and were last known to be inside the backpack while it was in police custody. As of publication, the keys have not been returned, nor has any documentation been provided explaining their disappearance.

Despite this, city authorities have threatened to tow the individual’s vehicle for failing to move it—an action he says is impossible without the missing keys.

Civil-rights attorneys say towing a vehicle under such circumstances could constitute deprivation of property without due process and raise spoliation concerns if the vehicle is connected to disputed law-enforcement actions.

Federal Statutes Implicated

In his report to the FBI, the complainant states that the conduct described may implicate multiple federal statutes, including:

- 18 U.S.C. § 641 (misuse or conversion of government information),

- 18 U.S.C. § 1030 (unauthorized or exceeded access to protected computer systems), and

- 18 U.S.C. § 371 (conspiracy to misuse federal systems).

He emphasized that he is not making charging decisions but is reporting facts that warrant federal review.

A Broader Civil Liberties Question

At the center of the controversy is a question with implications far beyond one individual case: Are emergency shelters being used—intentionally or not—as gateways for law-enforcement screening, and are federal criminal databases being accessed outside lawful purposes during crises?

Civil-liberties advocates warn that blurring the line between humanitarian aid and law enforcement risks chilling people from seeking help during emergencies, especially unhoused individuals or those with past system involvement.

Emergency conditions, they note, do not suspend constitutional protections or federal data-access rules.

Public Record, Public Accountability

The FBI complaint was made contemporaneously creating a timestamped record before further enforcement actions—such as towing—could occur. The reporting individual has also issued formal preservation demands to prevent destruction or alteration of evidence.

As of publication, neither the American Red Cross nor local authorities have publicly addressed whether any NCIC query was run, who initiated it, or whether any federal criminal-justice data was accessed or shared.

What remains undisputed is the public promise made on January 24: that the warming shelter was open to anyone, with no screening.

Whether that promise was honored—and whether federal law was violated in the process—is now a matter of federal record.

Discover more from We The People News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Breaking News

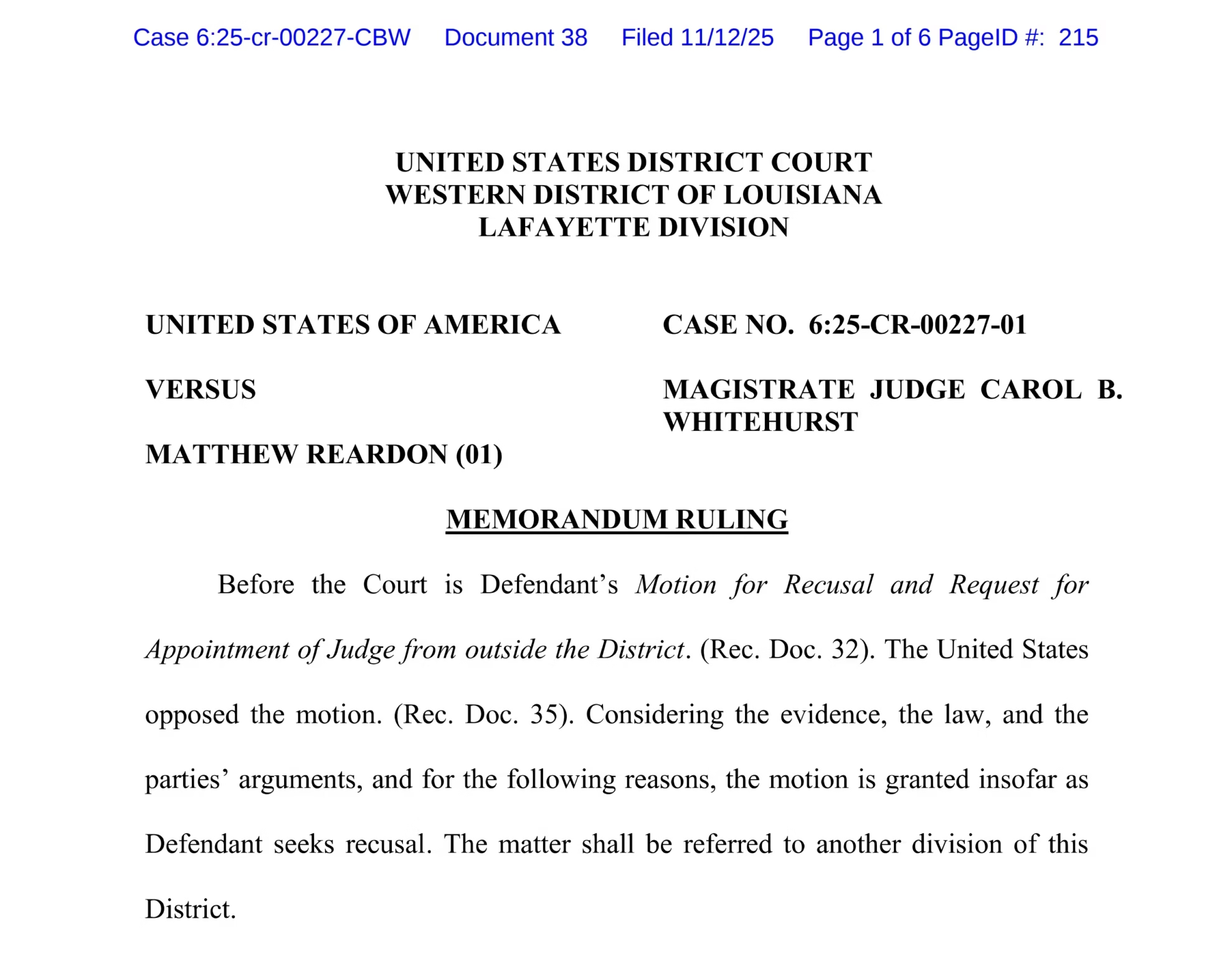

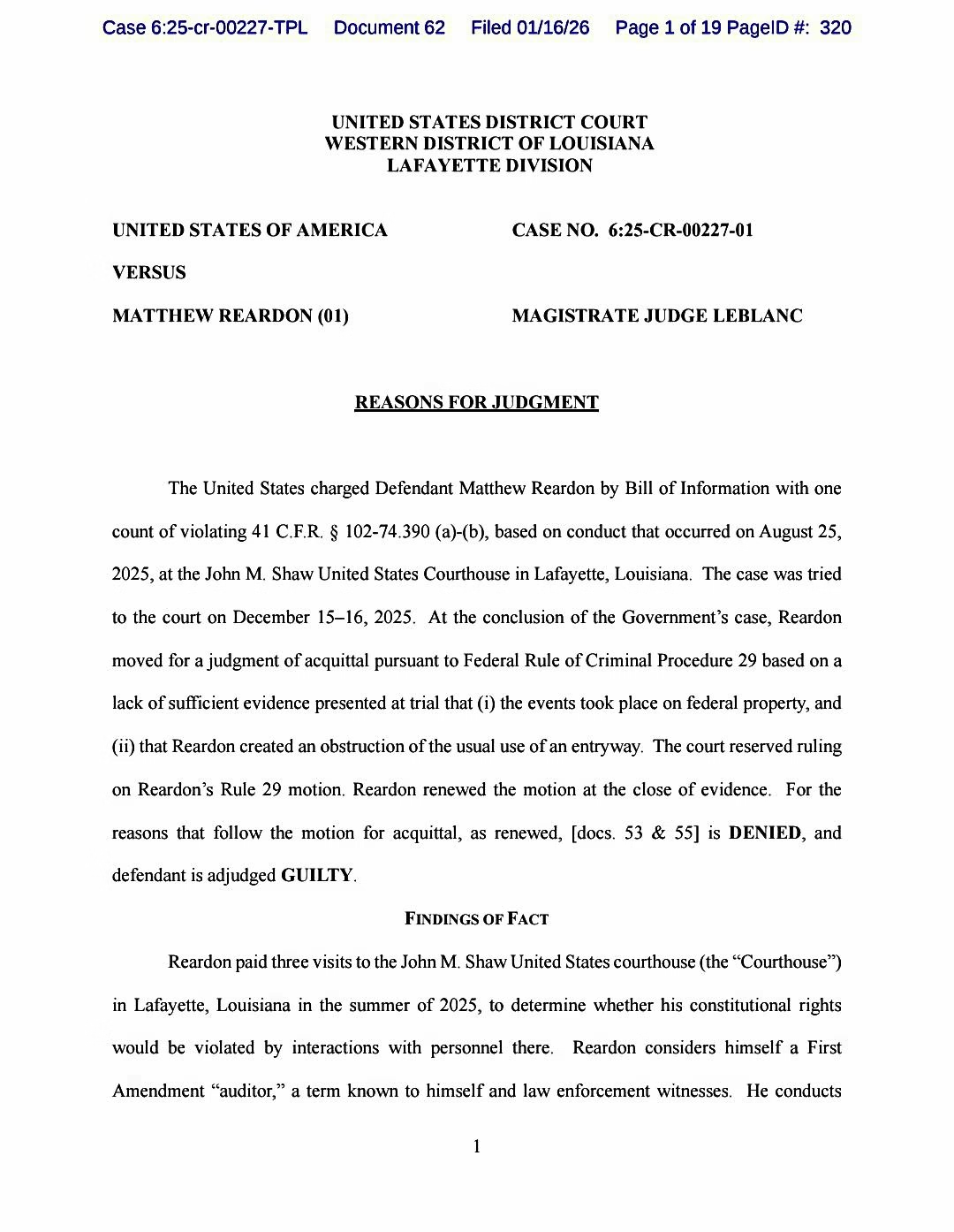

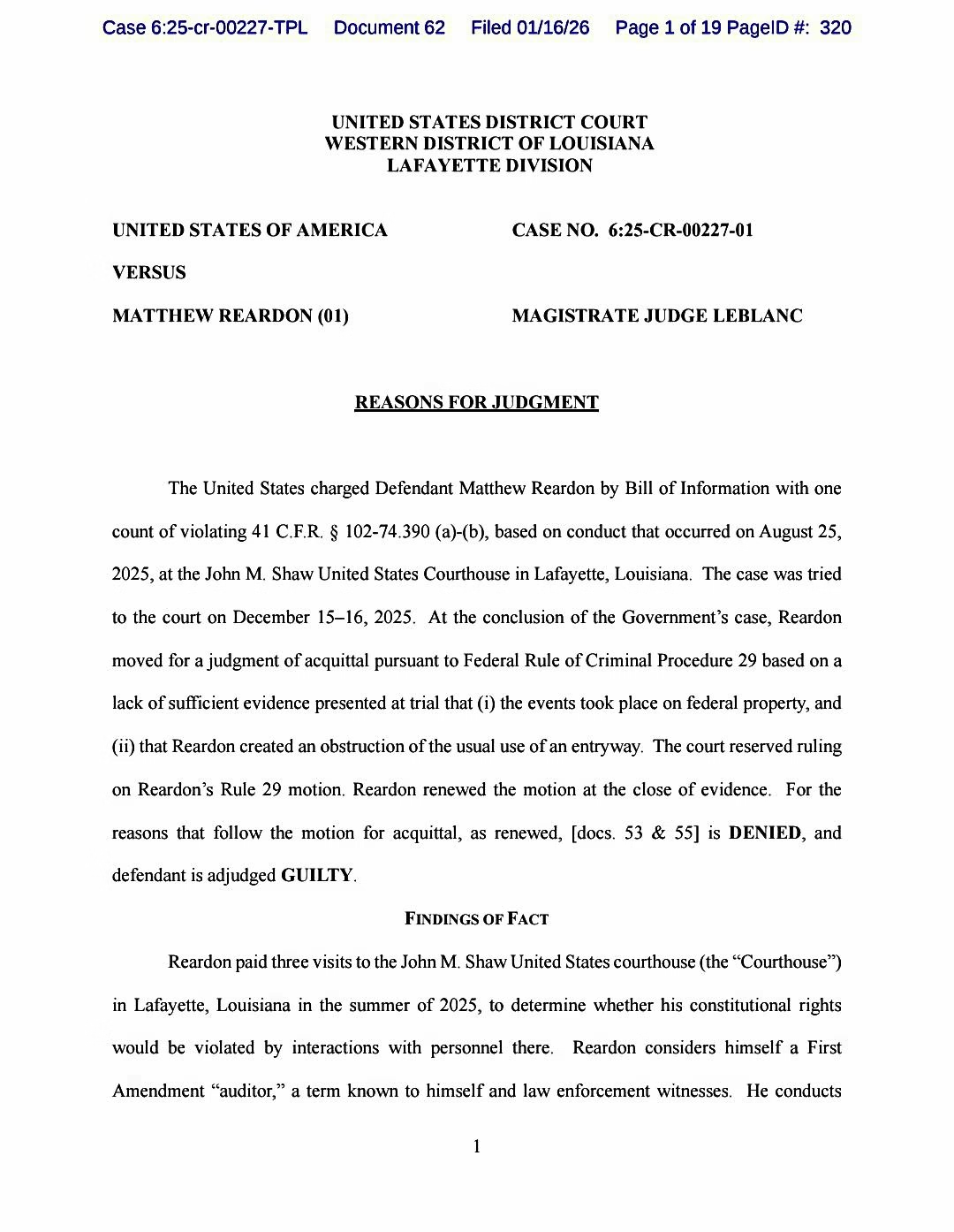

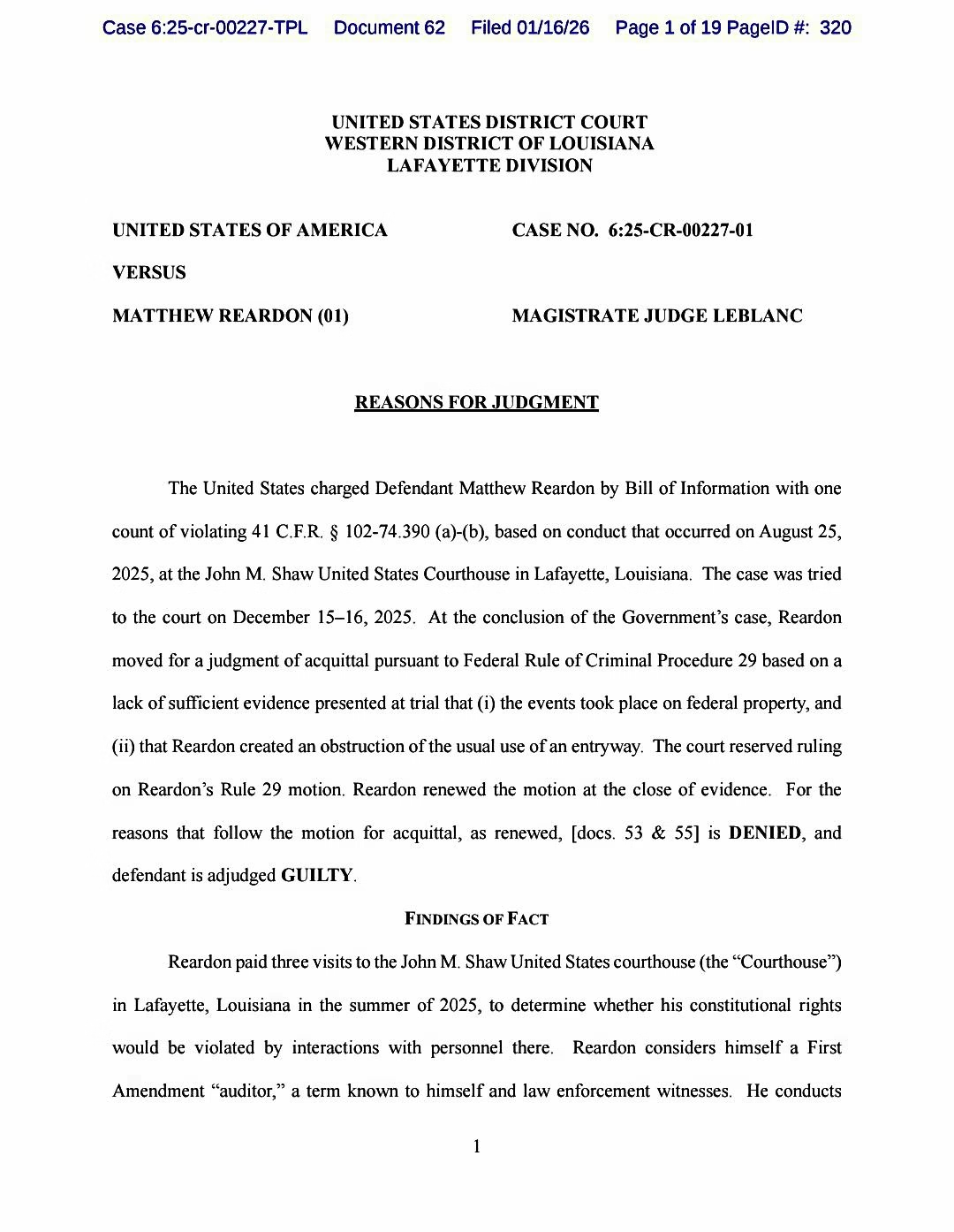

MAJOR VERDICT | How the Court Bent Law, Facts, and Time to Save the Government

By Matthew Reardon| We The People News

The January 16, 2026 “Reasons and Judgment of Conviction” should trouble anyone who still believes courts exist to restrain government power rather than protect it.

What follows is not a disagreement with a judge’s discretion. It is a point-by-point exposure of how law was contorted, evidence was excused away, and constitutional standards were quietly lowered to preserve a prosecution that should never have survived.

This ruling was not merely wrong. It was constructed.

1. The Court Excused Destroyed Evidence Instead of Punishing It

The most glaring defect appears immediately: the court accepted the government’s claim that critical video evidence was “not preserved due to technical error.”

That evidence was not peripheral. It went to the heart of the case. It showed U.S. Marshals waving me forward, directing my movement, and initiating the interaction later characterized as criminal.

This footage was requested. Timely. Repeatedly. On the record.

The law on this is settled. When the government loses or destroys materially exculpatory evidence—especially after notice—it does not receive deference. It receives sanctions. In many cases, dismissal.

Instead, the court did the opposite. It credited the government’s explanation without scrutiny and then proceeded as if the evidence never mattered.

That is not neutral adjudication. That is insulation.

2. The Court Erased Entrapment by Pretending It Wasn’t Raised

Entrapment is not a buzzword. It is a doctrine grounded in the idea that the government may not manufacture crimes by inducing conduct it then punishes.

The record shows federal officers initiating contact, signaling me forward, escalating the encounter, and only enforcing once criticism intensified.

The ruling does not meaningfully analyze this.

There is no serious inquiry into inducement.

No examination of officer conduct.

No assessment of whether the alleged violation would have occurred but for government prompting.

Instead, entrapment is treated as if it barely exists—mentioned only obliquely, then discarded.

That omission is not accidental. It is necessary for the conviction to stand.

3. The Court Rewrote “Obstruction” to Mean “Possibility”

The regulation at issue criminalizes unreasonable obstruction of entrances.

The court never identifies a single person who was blocked.

Never finds a delayed entry.

Never cites a disrupted operation.

Why? Because none occurred.

The door was locked.

Marked “emergency exit only.”

Not used by the public.

To overcome this, the court substitutes speculation for fact—what could have happened, what officers felt, what security imagined.

That is not proof beyond a reasonable doubt. It is conjecture elevated to conviction.

Courts do not convict people for what might have occurred. At least, they are not supposed to.

4. The Forum Analysis Is a Legal Shell Game

The ruling quietly downgrades the forum.

While acknowledging that courthouse steps are traditionally public, the court effectively treats the immediate exterior entrance area as something less—without citing a statute, regulation, or posted restriction converting it into a limited or nonpublic forum.

This maneuver matters. Once the forum is downgraded, constitutional scrutiny weakens. Government discretion expands.

But forum status is not decided by convenience. It is decided by history, access, and use.

The ruling offers none of that analysis—only assertion.

5. “Content Neutrality” Is Asserted, Not Proven

The court insists enforcement was content neutral.

The record says otherwise.

Recording was tolerated—until it documented Marshals.

Speech was tolerated—until it criticized Marshals.

Presence was tolerated—until the message became inconvenient.

Neutrality is not declared by judges. It is demonstrated by facts. And the facts here show escalation only after expressive activity crossed a line of criticism.

That is classic retaliatory enforcement.

6. The Court Pretended Speech and Conduct Are Separable

This ruling depends on a fiction: that speech and conduct can be surgically separated when enforcement is triggered by expression.

Protest is conduct.

Journalism is conduct.

Recording government officials is conduct.

The First Amendment protects these activities precisely because they occur in physical space and real time.

By pretending the case was about “conduct alone,” the court avoids confronting the constitutional problem it created. O and lets not forget about the many times throughout the order the judge made some type of reference to my language, even emphasized it. He can try to bend and twist it for some other reason, but that is a farce and this judgement bears weight to that. The Government got caught with its pants around its ankles. They got exposed and publicly criticized for it. This is what this retaliatory prosecution was all about.

7. The Missed Deadline Tells the Truth the Ruling Hides

The court ordered its own deadline: by or before January 15th.

It missed it.

Judges do not miss deadlines on easy cases. They miss them when facts conflict with outcomes.

The delay betrays hesitation.

The hesitation betrays doubt.

The doubt betrays the ruling.

This was not a clear conviction. It was a salvaged one.

8. Why This Conviction Was the Government’s Best Outcome—and Its Worst Mistake

An acquittal would have buried misconduct quietly.

A conviction creates a record.

This ruling now travels—to appellate judges not embedded in this courthouse, not invested in excusing Marshals, not tasked with justifying a prosecution built on missing evidence and speculative harm.

In trying to save the government, the court exposed it.

So yes, I will say this plainly.

Thank you, Judge Thomas Leblanc

Thank you for choosing a ruling that can be reviewed, reversed, and cited.

Because this case is no longer about me.

It is about whether the federal government can bait citizens, destroy evidence, criminalize journalism, and rely on judicial indulgence to make it all disappear.

That question is now on the record.

And it will be answered.

Discover more from We The People News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

-

Breaking News4 years ago

Breaking News Alert! A Chilling Warning to All Citizens particularly Journalists & Reporters in North Mississippi

-

Audits and Encounters1 year ago

Audits and Encounters1 year agoStaged DWI Arrest of Journalist Exposes Deep Government Corruption

-

Lafayette County Racket1 year ago

New Song- False Witness

-

Audits and Encounters3 years ago

Audits and Encounters3 years agoVictory for Transparency! Batesville, MS Reverses Controversial Ordinance Banning Video Recording in City Buildings

-

Breaking News2 months ago

Breaking News2 months agoMAJOR VERDICT | How the Court Bent Law, Facts, and Time to Save the Government

-

Breaking News1 year ago

Breaking News1 year agoAttack on the Press: Journalist Trapped, Railroaded, and Imprisoned in Mississippi